This article explores the essential role of instrument transformers (CTs and VTs) in substations, their construction, accuracy factors, and safety considerations.

Instrument transformers (ITs) are specialized transformers whose main role is to step down high currents or voltages in power systems to safe, standardized levels for metering, protection relays, SCADA, and control circuits, while maintaining proportionality and phase relation. They isolate measurement/protection circuits from dangerous high voltages/currents and ensure the integrity of measurement and protective operations.

In substations, two primary families are used:

- Current Transformers (CTs)

- Voltage Transformers / Potential Transformers (VTs / PTs / CVTs)

Current Transformers (CTs)

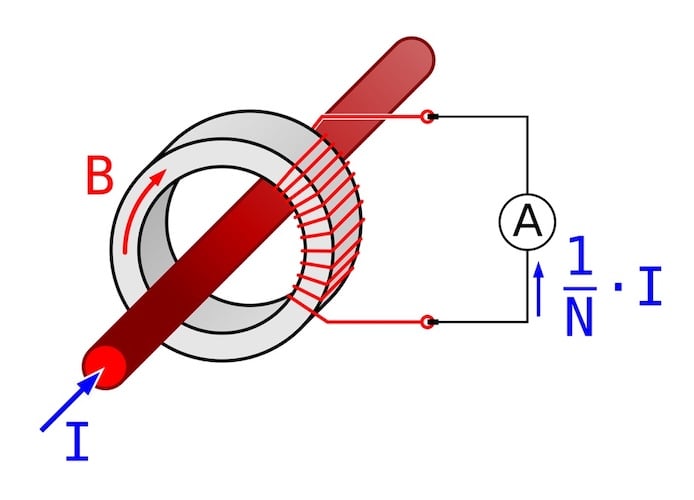

Current transformers convert a primary line current Ip to a reduced, proportional secondary current Is for metering and protection. Their two primary roles are (a) provide an accurately scaled current to meters and protection relays under normal and overload/fault conditions, and (b) isolate the high-voltage primary from low-voltage secondary circuits for measurement and protection equipment.

Typical construction variants include wound CTs (multiple primary turns or single-turn through-bore), bar-type CTs (single conductor through a window), bushing-type CTs (integral to transformer bushings), and split-core CTs for retrofit service. CTs are specified by nominal ratio (such as 1000/5 A), accuracy class (metering classes such as 0.1, 0.5; protection classes such as 5P10, 10P20), and rated burden (VA) or accuracy limit factor for protection CTs.

- Wound CT: Primary has actual wound turns, often used for smaller primary currents or special configurations.

- Bar or Solid-core CT: Primary is a straight bar (one turn) passing through the CT core window; core is wound only on the secondary side.

- Bushing-type CT: Integrated into high-voltage bushings, usually in GIS or transformer bushings; conductor through bushing acts as CT primary.

Figure 1. Current transformer for operation on 110 kV grid. Image used courtesy of Wikipedia.

CT Accuracy

CT accuracy is affected principally by the core magnetizing characteristics (magnetizing current), the secondary burden (load impedance connected to the secondary), and the presence of remanent magnetization (residual flux) in the core. Two error types are usually defined:

- Ratio error—the steady-state deviation of the scaled secondary current from the exact proportional value

- Phase displacement—the angular difference between the primary current vector (referred to the secondary) and the actual secondary current vector (important for power measurements).

An expression for ratio error (in percent) is:

$$text{Ratio error (%)} = frac{K_nI_s – I_p}{I_p} times 100 %$$

where Kn is the rated current ratio (for a 1000/5 CT, Kn =200), Ip is the instantaneous measured primary current, and Is the measured secondary current.

CT accuracy classes include metering classes ( 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 3) and protection classes ( 5P10, 10P20). “P” indicates protection class; the number ( 10) is the accuracy limit factor (how many times rated current the CT remains within specified composite error). For example, class 5P10 means that up to 10 times rated current, composite error (ratio + phase) must be within 5%.

Figure 2. Current transformer operation. Images used courtesy of Wikipedia.

Saturation Limits and Special Behavior

CT cores are designed to operate in the linear portion of the magnetization curve, but under fault conditions the magnetic flux can rise above the knee point, pushing the core into saturation. Once saturation occurs, the secondary current no longer scales proportionally with the primary, leading to waveform distortion, clipping, and potentially significant errors in protection relays or metering devices.

The risk of saturation increases with higher primary currents, large burdens on the secondary, and residual magnetization (remanence) from prior fault events. Residual flux can shift the operating point on the B–H curve, making the CT saturate earlier in subsequent faults. To mitigate this, protection-class CTs are manufactured with larger cross-sectional core areas and higher-quality steels to delay saturation. Utilities may also apply demagnetization procedures (such as applying an alternating current that is gradually reduced to zero) after severe faults to restore symmetrical flux behavior.

The instrument security factor (ISF or Fs) provides a standardized measure of CT performance under overload. Defined in IEC 61869-2, ISF quantifies the level of overcurrent up to which the CT can maintain its specified accuracy class without exceeding a composite error of 10%. For example, a CT marked Fs = 10 must sustain less than 10% error at ten times its rated primary current under rated burden. This is particularly important for metering CTs: the security factor ensures that during fault conditions, the CT limits secondary current to protect connected meters from damage, while still supplying usable information for relays.

CT Safety and Burden

NEVER open a CT secondary while the primary is energized. If the secondary circuit is opened the CT has no closed path for the magnetizing flux-produced secondary current; the core’s flux rises until very high voltages appear across the open secondary. These voltages can puncture insulation, produce dangerous flashover and create lethal voltages on the secondary wiring. This hazard is a fundamental rule in CT handling and is emphasized in standards and vendor guides.

Also, CTs must be connected to their rated burden: secondary burdens are specified in VA (such as 5 VA, 15 VA, 30 VA). Exceeding rated burden increases ratio and phase errors; extremely high burden can cause unacceptable errors or heating. For protection CTs the accuracy limit factor (ALF) is used to specify acceptable performance up to certain multiples of rated current.

- Protection CTs: designed to remain linear up to high multiples of rated current (high ALF) so relays see accurate fault currents.

- Metering CTs: optimized for low error at rated current with tighter percentage classes (0.1, 0.5, etc.), but they may saturate if subjected to heavy faults.

Current Transformer (CT) Ratio Error Example

A protection CT has nominal ratio 1000 : 5 A. At a particular instant the primary line current is measured as Ip = 800 A and the CT secondary current is measured as Is = 4.02 A. Calculate the CT ratio error in percent using the standard ratio-error definition.

Solution

Compute the rated current ratio Kn:

$$K_n = frac{1000}{5} = 200$$

Compute the ideal (expected) secondary current at the given primary current:

$$I_s = frac{I_p}{K_n} = frac{800}{200} = 4.0 text{ A}$$

Apply the ratio-error formula:

$$text{Ratio error (%)} = frac{(200 times 4.0) – 800}{800} times 100 = 0.5%$$

A +0.50% error means the secondary current is 0.5% larger than the ideal scaled value at that operating point. Whether this is acceptable depends on the CT accuracy class and application (metering vs protection).

Voltage Transformers / Potential Transformers

VTs (or PTs) transform high primary voltages (like tens or hundreds of kilovolts) to lower, proportional secondary voltages (such as 110 V or 100 V) for metering, relaying, and measurement devices. They are connected in parallel with the primary circuit; their secondary circuit can be left open when the primary is live, but must never be short-circuited.

Voltage transformers must maintain accurate voltage ratio and phase angle with minimal distortion, while presenting minimal load (burden) to the primary system.

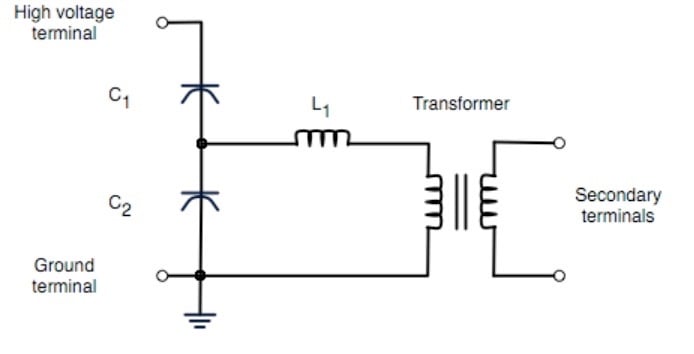

A specialized variant at very high voltages is the Capacitive Voltage Transformer (CVT), which uses a capacitive divider followed by a small transformer or electronic circuitry to achieve high voltage ratio in a space- and cost-efficient manner (especially over EHV transmission).

Figure 3. Capacitor voltage transformer (CVT). Image used courtesy of Hitachi Energy.

Voltage Ratio Error and Phase Displacement

Analogous to CTs, VT performance is characterized by ratio error and phase displacement. A ratio-error definition (expressed in percent) is:

$$text{Ratio error (%)} = frac{K_t V_s – V_p}{V_p} times 100 %$$

where Kt is the rated voltage ratio (for a 110 kV / 110 V VT, Kt = 1000), Vp is the actual primary voltage, and Vs the measured secondary voltage.

Phase displacement (in minutes or degrees) quantifies the angular error between primary and secondary phasors and is critical for accurate kW/kVAr metering and for relay phase comparison schemes. Vendor and standards documents specify allowable ratio and phase errors by class and burden.

| Class | Ratio Error (%) | Phase Displacement (min) |

| 0.1 | ± 0.1 | 5 |

| 0.2 | ± 0.2 | 10 |

| 0.5 | ± 0.5 | 20 |

| 1 | ± 1 | 40 |

| 3P | ± 3 | 120 |

Table 1. Voltage Transformer Accuracy Classes

Insulation and Overexcitation Risks

VTs, especially at high voltages, must have strong insulation to safely withstand system surges (lightning, switching) and overvoltage conditions. Overexcitation or resonance (especially in lightly loaded or ungrounded systems) can push flux beyond linear core limits, potentially causing core saturation or even destructive magnetic heating (ferroresonance).

Failure by overexcitation is a known design hazard. For example, VTs connected line-to-ground in ungrounded systems must consider parallel capacitances and risk of parallel resonance.

CVT Behavior And Burden

CVTs introduce additional dynamic behavior (tuning of the capacitive divider and series reactor) so their transient response and harmonic behavior differ from electromagnetic VTs; CVTs commonly require damping resistors to limit switching transients and to maintain acceptable accuracy under switching impulse and transient conditions. Burden on VTs is usually expressed in VA—large burdens (many relays, long cable runs) degrade VT accuracy and increase phase displacement.

Figure 4. Capacitor voltage transformer (CVT) circuit diagram. Image used courtesy of Wikipedia.

Voltage Transformer Ratio Error Example

A VT is rated 110 kV : 110 V. Under measurement the primary line voltage is Vp = 110,000 V (nominal) and the VT secondary measures Vs = 109.6 V. Calculate the VT ratio error in percent.

Solution

Compute the rated voltage ratio Kt:

$$K_t = frac{110,000}{110} = 1000$$

Compute the ideal (expected) secondary voltage at nominal primary:

$$text{Ideal }V_s= frac{V_p}{K_t} = frac{110,000}{1000} = 110.0 text{ V}$$

Apply the ratio-error formula:

$$text{Ratio error (%)} = frac{(1000 times 109.6) – 110,000}{110,000} times 100 % = -0.36 %$$

A −0.364% error means the VT secondary voltage is 0.364% lower than the ideal proportional value, effectively indicating that the VT is undervaluing the primary voltage. Whether this is acceptable depends on the permissible limits defined by the VT’s accuracy class and the precision requirements of the connected metering or relaying equipment.

Key Takeaways

Instrument transformers (ITs) such as current transformers (CTs) and voltage transformers (VTs) play a crucial role in modern power systems by transforming high levels of current and voltage to safe, manageable levels for metering, protection, and control applications. Their functionality not only ensures the reliability and accuracy of power measurements but also enhances the safety of electrical systems by isolating sensitive devices from high-voltage circuits.

Understanding characteristics such as accuracy, burden, saturation limits, and the risks associated with opening secondary circuits is essential for the effective deployment and operation of these transformers. As power networks evolve to accommodate renewable energy sources and smart grid technologies, the role of instrument transformers will continue to be pivotal, requiring ongoing advancements in their design, accuracy, and safety measures.

Featured image used courtesy of Hitachi Energy.