Learn how silicon carbide power modules can ensure energy efficiency and weight optimization in hybrid-propulsion trains.

This article is published by EEPower as part of an exclusive digital content partnership with Bodo’s Power Systems.

As we inch towards a future of net-zero emissions, diesel trains are being replaced by hybrid-propulsion trains. These can operate with the support of electricity from overhead lines or—where electrification of railway track is not feasible—from on-board batteries or hydrogen fuel-cells. For such hybrid-propulsion trains, energy efficiency and weight optimization are of crucial importance. Both can be delivered by silicon carbide power modules.

Getting on track with a net-zero scenario requires the electrification of diesel trains. This can be done by powering the electrified trains via overhead lines or third-rail systems. Where electrification of the railway track is not viable, hybrid propulsion trains are needed. These are the trains that, on non-electrified rail sections, can be powered from onboard batteries or hydrogen fuel cells.

Image used courtesy of Adobe Stock

Energy-efficient power semiconductors are at the core of the transition to green railway traction, since they contribute to energy savings in multiple parts of the train, for example:

- Converting energy from the overhead line to the motor: that is, in the line converter between the overhead line/catenary and the DC-link capacitor, as well as in the motor inverter, between the DC-link capacitor and the train motor

- Transitioning power from the battery or hydrogen fuel cell to the motor: that is, in the DC-DC converter between the battery or hydrogen fuel cell and the DC-link capacitor; and in the motor inverter, between the DC-link capacitor and the train motor

- Powering auxiliary systems like air conditioning, ventilation, and lighting.

While energy efficiency is often top-of-mind, trains also need to be able to operate in extreme conditions with demanding mission profiles over service lifetimes of 35 years or more. Harsh climates with freezing temperatures, heat, and humidity, as well as the frequent acceleration and braking required by trains, can cause thermomechanical stress and result in aging. Therefore, in addition to being energy efficient and providing high power density, power semiconductors need to offer high quality and reliability.

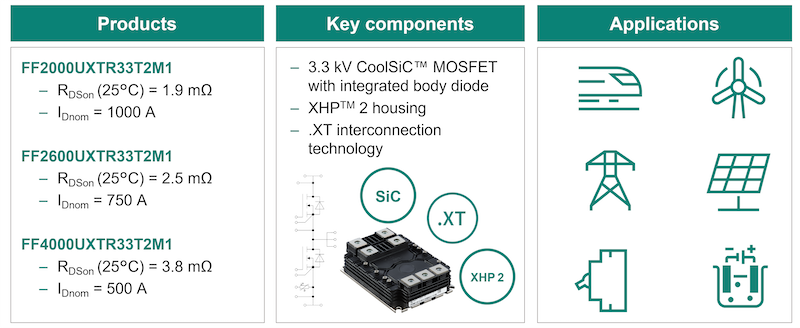

Figure 1. The XHP™ 2 CoolSiC MOSFET 3.3 kV with .XT technology product family is designed to deliver high power to demanding applications like railway traction, wind power generation, photovoltaic inverters, energy storage systems and beyond. Image used courtesy of Bodo’s Power Systems [PDF]

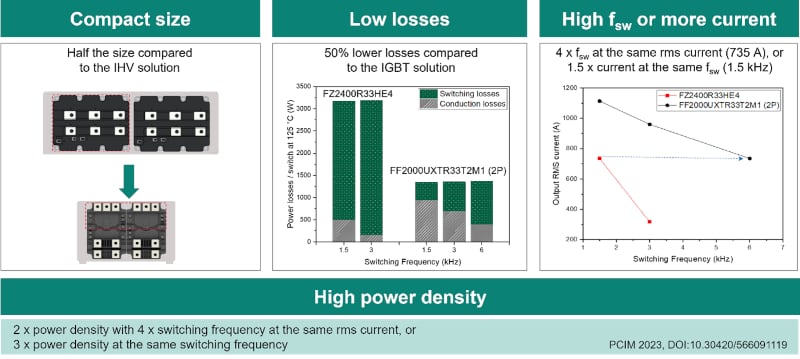

Figure 2. The key features of the XHP 2 CoolSiC MOSFET 3.3 kV with.XT technology can be directly translated to multiple system benefits. Image used courtesy of Bodo’s Power Systems [PDF]

Reducing Losses, Weight, and Size

The new 3.3 kV-rated modules with CoolSiC™ technology (Figure 1) enable significant energy savings in industrial power generation, in solar parks and wind farms, in power transmission and distribution, as well as in consumption, where high power in the megawatt range is needed. Equipped with these SiC modules, a single locomotive can save about 300 MWh per year compared to previous silicon-based components, which is approximately equivalent to the annual energy consumption of 100 single-family homes.

Compared to silicon power semiconductors, silicon carbide power semiconductors have significantly lower power losses and therefore enable energy-efficient traction converters. In a field test organized by Siemens Mobility and the Munich public transportation company SWM [1], Infineon’s XHP™ 2 CoolSiC power modules demonstrated a 10 percent increase in energy efficiency compared to silicon modules.

In addition, Infineon’s latest silicon carbide power modules deliver high power density, enabling more compact traction converters (~ 10 – 25 percent volume reduction [2]). Moreover, by enabling traction converters to operate at high switching frequencies, silicon carbide power modules enable a reduction in the size and weight of various bulky magnetic components in the system.

3.3 kV-rated SiC chips housed in symmetrical and low-inductive (10 nH) XHP 2 package have been designed for fast switching (~18 kV/µs), leading to reduced dynamic losses. When comparing the performance of a motor inverter based on the 3.3 kV IGBT IHVB solution with the performance of a motor inverter based on the 3.3 kV SiC XHP 2 modules (Figure 2), it becomes evident that the SiC solution has a 50 percent smaller footprint and shows 50 percent lower total losses compared to the IGBT solution. This results in 50 percent more output current at the same switching frequency (1.5 kHz) or the same output current at a four times higher switching frequency (6 kHz instead of 1.5 kHz). [3]

An additional performance benefit can be achieved by taking advantage of the so-called synchronous rectification mode (reverse channel operation). By opening the channel in 3rd quadrant and reducing the time during which the load current is freewheeling through the body diode (at the beginning and the end of the freewheeling phase), dynamic losses at elevated temperatures can be reduced by a further ~30 percent [4].

Energy efficiency and weight optimization are of crucial importance for hybrid propulsion trains. Both aspects help extend the range that these trains can cover when powered by batteries or fuel cells. In the case in which there is no need for extending the catenary-free mileage of the train, improved energy efficiency and weight reduction can be used to decrease the size of the battery, which will result in corresponding cost-down. This is important because batteries are still the main cost drivers of such trains.

Finally, silicon carbide power semiconductors contribute to quieter train systems. On one hand, low-loss, energy-efficient silicon carbide semiconductors require less cooling, which allows for simplified cooling systems (for example, passive air cooling instead of forced air cooling), meaning the fans can be eliminated and cooling made quieter. On the other hand, operating traction converters at higher switching frequencies makes it possible to reduce the audible noise emanating from the train motor.

Enhancing the Lifetime in the Application

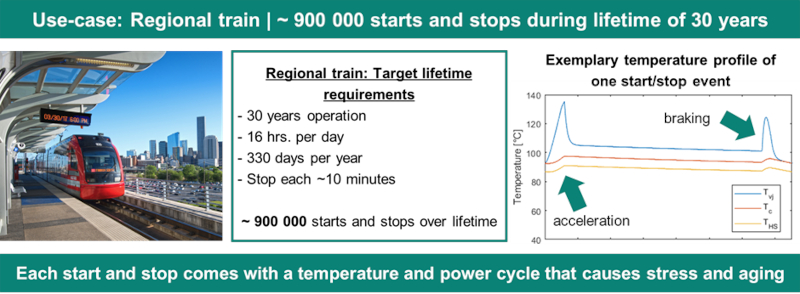

In addition to power density, energy efficiency, and weight optimization, certain applications like railway transportation also require high cycling capability from the power modules. To understand this, let’s consider an example of a regional train. During its service lifetime of about 30 years, such a train will make approximately 900,000 start and stop events.

Each of these events comes with a temperature and power cycle, which causes thermomechanical stress on the interconnection layers in the power module, for example, on the chip’s bond wires or on the die-attach layer just underneath the chip. This thermomechanical stress causes aging and reduces the lifetime of the power modules in the application (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The frequent starts and stops of a regional train place a heavy cycling load on the power electronics. Each start and stop comes with a temperature and power cycle that causes stress and aging. Image used courtesy of Bodo’s Power Systems [PDF]

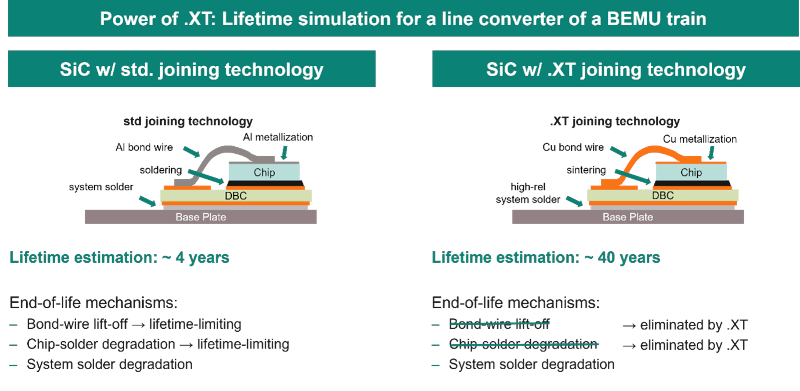

Figure 4. Lifetime simulation for a line converter of a BEMU train. The .XT technology enhances the load cycling capability of the product and extends its lifetime in the application. Image used courtesy of Bodo’s Power Systems [PDF]

Infineon’s XHP 2 CoolSiC MOSFET solution addresses this issue by combining high-power silicon carbide technology with .XT interconnection technology. The .XT technology specifically targets the layers most affected by thermomechanical stress during cycling, such as bond wires and die attach, making them more robust and reliable. This boosts the power cycling capability and extends the lifetime of the product in the application.[5]

To illustrate the power of .XT, a lifetime simulation based on the exemplary mission profile of a line-converter in a regional hybrid-propulsion train, was performed. Infineon compared SiC with standard joining technology (Al bond-wires, Al front-side metallization of the chip, soldered chip on a substrate, system solder) and SiC with .XT (Cu bond-wires, Cu front-side metallization of the chip, sintered chip on a substrate, hirel system solder).

The simulation results showed that.XT extended the lifetime of the power module from around four years in the case of SiC with standard joining technology to approximately 40 years in the case of SiC with XT. This improvement demonstrates that.XT enables the full utilization of silicon carbide at higher junction temperatures, in applications with demanding mission profiles, like railway traction (Figure 4).

High Ruggedness: Surge Current and Short Circuit Robustness

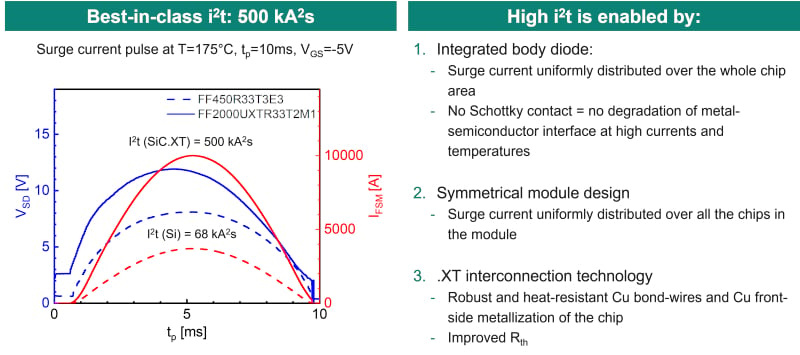

To allow system designers more freedom in handling failure cases, 3.3 kV SiC XHP 2 power modules have been designed for high surge current and short circuit robustness.[5]

High switching frequencies of SiC converters enable the use of smaller, more efficient transformers characterized by low ohmic resistances and stray inductances. Since the parasitic stray inductance of transformers helps limit surge current levels in the application, changing to low-inductive transformers means that the system needs to be able to cope with higher surge current levels. To enable this, 3.3 kV SiC XHP 2 modules have been designed for higher i2t ruggedness (500 kA2s at Tvj=175 °C, tp = 10 ms).

Figure 5 shows a comparison of surge current waveforms for Si with standard interconnection technology (FF450R33T3E3) and SiC with .XT (FF2000UXTR33T2M1). Superior surge current capability of FF2000UXTR33T2M1 module is enabled by the combination of a robust integrated body diode, symmetrical XHP 2 module design and .XT interconnection technology.

Figure 5. High i2t ruggedness of 3.3 kV SiC XHP 2 is enabled by the combination of a robust integrated body diode, symmetrical XHP 2 module design and .XT interconnection technology. Image used courtesy of Bodo’s Power Systems [PDF]

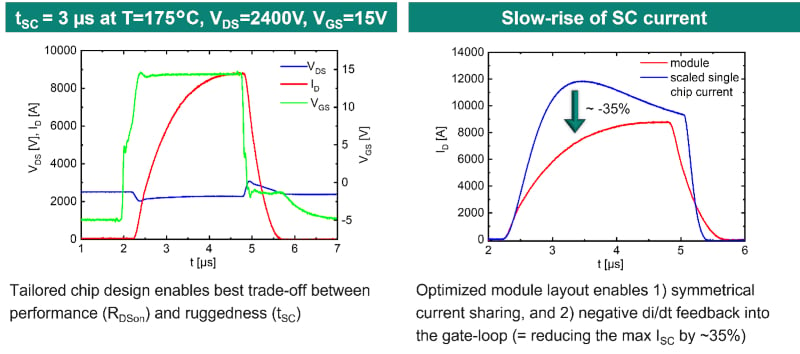

Short-circuit withstand time is a commonly sought-after requirement in railway traction application, which allows the gate driver sufficient time to react in case of an unforeseeable failure. During the development of the 3.3 kV CoolSiC MOSFET, special care was taken to design a chip with low RDS(on) and sufficient short-circuit withstand time (tSC = 3 µs at VDS = 2400 V, Tvj=175 °C, Vgs = 15 V).[6]

In addition, the XHP 2 power module has been designed to slow down the short-circuit current rise by introducing negative feedback into the gate-loop. The maximum short-circuit current measured on the module level is about 35 percent lower compared to the short-circuit current from scaled single-chip measurements (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Short circuit ruggedness is enabled by optimized chip and module design. Image used courtesy of Bodo’s Power Systems [PDF]

Paralleling of 3.3 kV SiC XHP 2

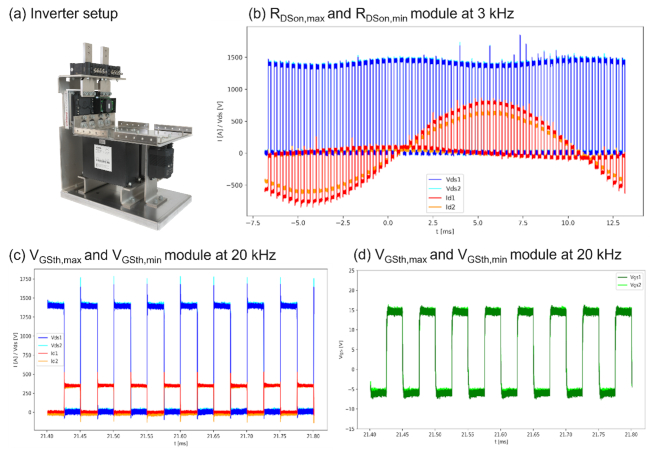

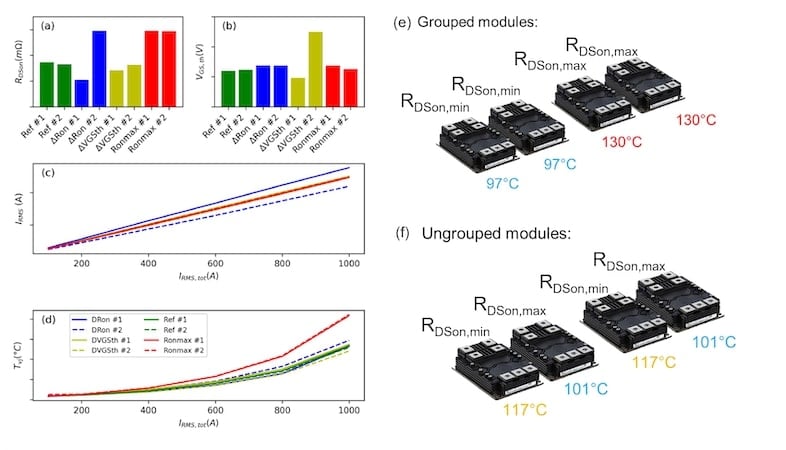

Power-hungry applications often require paralleling of power modules. This can be a complex task, requiring careful consideration of various technical aspects, such as power system design as well as matching the electrical parameters of paralleled modules. Paralleling of 3.3 kV SiC XHP 2 power modules has been thoroughly investigated [7], with the main conclusion: due to the strong effect of positive temperature coefficient of RDS(on), 1) the current mismatch between the paralleled modules is minimized; 2) randomization of modules results in better thermal performance compared to grouping of symmetrical modules, and therefore 3) no grouping of symmetrical modules for paralleling is necessary.

3.3 kV SiC XHP 2 power modules benefit from a positive temperature coefficient of the on-state resistance RDS(on), which results in homogeneous current sharing and temperature distribution in parallel operation (Figure 7). The module with the smaller RDS(on) will initially carry the larger current, leading to higher temperature. This will increase the RDS(on), which will result in a negative feedback loop with effectively smaller deviations in ΔRDS(on), junction temperatures ΔTvj and currents ΔID.

Figure 7. Easy paralleling of 3.3 kV SiC XHP 2 modules in inverter operation: no selection of modules for paralleling is needed. (a) Power electronic building block demonstrator used for the experimental validation of paralleling in inverter operation. More info on the setup can be found in [8]. (b) Exemplary ID (red, orange) and VDS waveforms (light blue, dark blue) over a sinusoidal period at fsw = 3 kHz show only 10 percent current mismatch for an unlikely, worst-case module pair w/ RDS(on)_max and RDS(on)_min. (c) Exemplary ID (red, orange) and VDS waveforms (light blue, dark blue) and (d) exemplary VGS waveforms (light green, dark green) for worst-case module pair w/ VGSth_max and VGSth_min. No dynamic current redistribution can be seen at fsw = 20 kHz. Image used courtesy of Bodo’s Power Systems [PDF]

Interestingly, both in simulation and experiment, we observe that selecting symmetrical modules for paralleling results in poorer thermal performance than random selection, as described in more detail in [7] and shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Experimental verification of thermal balancing in inverter operation: randomization of power modules results in better thermal performance than symmetric grouping. (a) RDS(on) parameters of 4 measured module pairs. (b) VGSth parameters of 4 measured module pairs. Green bars: reference module pair, with symmetrical RDS(on) and VGSth (typical values). Blue bars: Module pair with deviating RDS(on) and symmetrical (typical) VGSth. Yellow bars: Module pair with deviating VGSth and symmetrical (typical) RDS(on). Red bars: Module pair with symmetrical RDS(on) values (maximum values), and symmetrical (typical) VGSth values. (c) Current sharing among the paralleled modules as measured in inverter test: as expected, current mismatch (~10%) is observed for modules with maximum deviating RDS(on) values (blue lines). (d) Junction temperature variations among the paralleled modules as measured in inverter test: note that the highest junction temperature corresponds to the symmetrical module pair, with both modules having RDS(on)_max (red lines). (e) Simulation results of a 2-phase inverter with 2-fold parallelization, based on 4 modules: two modules with RDS(on)_min and two modules with RDS(on)_max. Grouping of modules for paralleling increases the chance of combining a pair of modules with high RDS(on) and resulting high Tvj. (f) Simulation results of a 2-phase inverter with 2-fold parallelization, based on 4 modules: two modules with RDS(on)_min and two modules with RDS(on)_max. Randomization of modules results in a more favorable thermal situation compared to the case in which modules with RDS(on)_max are grouped for paralleling.

For completeness, please note that the influence of the positive feedback loop for VGSth (lower VGSth → higher dynamic losses → higher temperature → lower VGSth), which might cause dynamic current imbalances, is not observed in our investigation, but it might play a role at very high switching frequencies. Figure 7c,d shows the paralleled operation of VGSth_max and VGSth_min modules at fsw = 20 kHz. No signs of dynamic current mismatch can be seen.

Conclusion and Outlook

The future of railway transportation is electric. High power technologies like Infineon’s XHP 2 CoolSiC MOSFET with .XT interconnection technology are paving the way toward this reality. By enabling energy-efficient, compact, quiet systems with enhanced lifetimes, these technologies are putting rail transport’s decarbonization on the right track.

References

[1] Siemens Mobility GmbH, “SiC semiconductor technology in tram: Siemens Mobility and Stadtwerke München successfully conclude test,” Siemens (Press Release), Dec. 3, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://press.siemens.com/global/ en/pressrelease/sic-semiconductortechnology-tram-siemens-mobility-andstadtwerke-munchen-successfully. [Accessed: Aug. 7, 2025].

[2] Siemens Mobility, “Silicon carbide – a material that developers dream about,” Siemens Mobility (Story Page), [Online]. Available: https://www.mobility.siemens.com/global/en/company/stories/ silicon-carbide-a-material-that-developers-dream-about.html. [Accessed: 7 Aug. 2025].

[3] J. Vishal, J. Czichon, and M. Bürger, “Efficient and Optimized Traction Converter Systems Enabled by the New 3.3 kV CoolSiC™ MOSFET and .XT in an XHP™ 2 Package,” PCIM 2023.

[4] M. Bürger, K.-H. Hoppe, K. Schraml, and A. Wedi, “The New XHP 2 Module Using 3.3 kV CoolSiC MOSFET and .XT Technology,” PCIM 2023.

[5] M. Bürger, T. N. Wassermann, and H. Foester, “Benefits of .XT interconnection technology for XHP2 module with 3.3 kV CoolSiC MOSFET,” PCIM 2024.

[6] C. Leendertz, M. Hell, G. Zeng, T. Ganner, T. Söllradl, P. Sochor, R. Elpelt, K. Schraml, D. Peters, „CoolSiC Trench MOSFET Chip Design for the 3.3 kV Class”, PCIM 2023.

[7] A. Fischer, M. Bürger, and D. Car, „Parallelization of XHP CoolSiC 3.3 kV devices”, PCIM 2025.

[8] J. Czichon, U. Schwarzer, N. Hoffmann, „Performance analysis of a PEBB demonstrator with high power 3.3 kV CoolSiC in XHP 2 for modern railway traction systems”, PCIM 2023

This article originally appeared in Bodo’s Power Systems [PDF] magazine.