Learn how to model and manage heat in 4-6.5 kV IGBT and SiC modules using coupled electro-thermal simulations for accurate cooling and reliable design.

IGBTs and newer SiC MOSFET technologies form the core of converters in multi-kV systems. These high-voltage power modules, operating between 4 and 6.5kV, are commonly used in applications such as HVDC converter stations, railway traction converters, medium motor drivers, and large industrial power systems. In such environments, the modules must efficiently manage megawatt-class power levels under demanding operating conditions, as any performance reduction or failure can result in expensive downtime for the system or reduced efficiency.

One of the key design challenges of the high-power module is thermal management. There are significant switching losses at high blocking voltages, especially during turn-offs, when the voltage increases due to high conduction of current.

Even though wide-bandgap SiC modules facilitate faster switching and lower conduction losses when compared to traditional Silicon IGBTs, the modules create step voltage changes that lead to localized heating in the interconnects surrounding the semiconductor and the semiconductor die. The downsizing of these modules to more power-dense packaging also limits thermal mass and heat dissipation, causing the junction temperature to be more sensitive to transient overload.

Increased Electrical Stresses

Adding to this challenge is the increased electrical stress on busbars, insulations, and substrates. In multi-kV modules, failure in the dielectric can result in both severe thermal runaway and degradation of the module’s performance. Since these modules are used in series or parallel configurations, a single device that has its thermal limits exceeded can affect the overall reliability of the converter system.

Due to these challenges, precision in thermal modelling is an essential part of the design process of these converter systems. Engineers, therefore, need to control and predict the behaviour of heat generated by these power modules under both transient and steady-state conditions.

This is where coupled thermal-electrical models come in, integrating detailed thermal impedance networks with power loss calculations to tackle not just the die, but also substrates, busbars, coolant channels, and heatsinks. With this model, the correct sizing of the power module cooling system can be effectively implemented, offering a safe operating limit and reduced risk of long-term degradation.

Figure 1. A CFD visualization of a radial heat sink showing how heat is distributed and how airflow swirls under forced convection. Image used courtesy of Wikimedia.

Understanding Electro-Thermal Coupling in HV Modules

Understanding thermal modelling starts with evaluating the electrical losses within power modules that generate heat and how this generated heat spreads across the module’s structure. In multi-kV IGBT and SiC MOSFET modules, switching and conduction losses play a significant role in shaping the thermal profile. The resultant rise in temperature must therefore be evaluated through the power module’s multilayered structure using equivalent thermal parameters.

During switching saturation, the voltage drop and resistance level as the load current passes through generate conduction loss, resulting in heat production. To obtain an accurate picture of the losses that generate heat, conduction, and switching losses in IGBT and SiC MOSFETs in these power modules, it can be evaluated.

IGBT conduction loss is assessed by considering the dynamic resistance (rCE), the average collector current, and the collector-emitter saturation voltage VCE(sat), which appears across the IGBT when it is fully turned on. The total IGBT conduction loss is therefore directly affected by the amount of load current, on-state voltage drop, and the duty cycle. These losses can therefore be evaluated as:

$$P_{cond,IGBT} = V_{CE(sat)} cdot I_{C,avg} + r_{CE} cdot I_{C,rms}^2$$

The voltage drop across an IGBT module in its on-state isn’t purely resistive, as it is influenced by both the collector-emitter saturation voltage, a fixed component due to the bipolar junction structure, and a variable average collector current component resulting from internal resistance, thereby providing a more accurate estimation of the total conduction loss across the full load range.

Once the conduction loss in the IGBT is evaluated, we can proceed to understanding and evaluating SiC MOSFET conduction losses, which are purely resistive and originate from the internal channel and drift region resistance of the MOSFET when it is in the on-state. The effective heating current directly influences these losses through the MOSFET. Since resistive heating is proportional to the square of the current, the RMS current defines the current that would result in the same thermal impact.

The on-state resistance (RDS(on)) is the drain-to-source resistance of the MOSFET when fully turned on. This resistance increases with junction temperature (Tj). Unlike silicon IGBTs, which exhibit a nearly constant voltage drop during conduction, the conduction loss in SiC MOSFETs increases linearly with temperature and quadratically with current, creating a positive electro-thermal feedback loop.

$$P_{cond,MOSFET} = I_{D,rms}^2 cdot R_{DS(on)}(T_j)$$

Building a Coupled Thermo-Electrical Model

Thermal modelling in HV power modules involves converting electrical losses, as described in the above subtopic, into temperature rise estimates that guide the design of liquid cooling systems or heat sinks. This is made possible using an equivalent thermal circuit that replicates the heat flow behavior using well-known electrical analogies.

Equivalent Thermal Circuits

Similar to an electrical network model, which describes the flow of current through capacitors and resistors, thermal network models represent the flow of heat through materials with specific heat capacities and conductivities. This allows the use of well-known circuit concepts for the analysis of complex heat flow patterns.

Thermal resistance Rθ measures the ease of heat flow through an interface or material, whereas thermal capacitance Cth quantifies the amount of heat energy that can be stored by a material for a specific change in temperature. When combined, these elements create a thermal RC network model that analyzes and predicts how power loss results in temperature increase over time in semiconductors.

| Electrical Quantity | Thermal Equivalent | Unit |

| Current (I) | Heat flow rate Q | W (J/s) |

| Voltage (V) | Temperature difference ΔT | °C or K |

| Resistance (R) | Thermal resistance Rθ | °C/W |

| Capacitance (C) | Thermal capacitance Cth | J/°C |

Table 1. Table illustrating equivalent thermal circuit

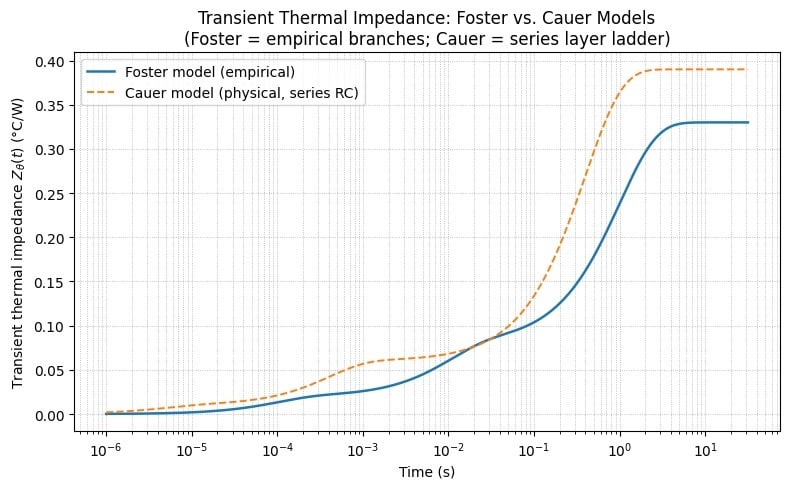

When modeling the transient thermal behavior in high-power modules, two primary approaches are typically used for representation: Foster and Cauer models. Foster empirical representation model directly derived from transient thermal impedance Zθ(t) curves provided from the power device’s datasheet.

The model represents the system as multiple RC branches that feature a unique time constant in thermal response, and this model is suitable for use in compact modeling and quick simulation, where detailed physical insight is not required. The lack of a direct physical connection results in the individual RC components lacking correspondence to the actual layers in the power module. Cauer’s physical representation model, on the other hand, models the layers of the power modules, such as baseplates, solder layer, substrate, heatsink, and semiconductor die, as sequential RC elements.

By capturing the heat flow through each stage of the thermal path, this model ensures precise spatial and material-specific accuracy. Cauer is therefore suitable for a multi-device module that shares a common cooling plate or baseplate, where there is significant heat spread and coupling effect.

Figure 2. Graph comparing Foster, sum of responses of parallel RC branches, vs Cauer curve approximated using a series ladder step-response form incorporating cumulative resistances. Image used courtesy of Bob Odhiambo.

Despite Foster and Cauer’s model being able to represent the thermal network in layers of power modules, their practical application becomes evident when the actual power dissipation is applied to the device, leading to a transient junction temperature response that represents how the semiconductor junction temperature rises in response to continuous power loss or a power pulse.

The thermal impedance of each RC branch determines the exponential pattern followed by the junction temperature that increases when constant power P is dissipated within the device. This thermal impedance is, therefore, evaluated as shown by considering the RC elements (n) that model the thermal response, the thermal resistance, and thermal capacitance of the i-th RC branch.

$$Delta T_j(t) = Sigma_{i=1}^n P cdot R_{theta i} cdot (1 – e^{-t/tau i})$$

Electrical-Thermal Co-Simulation Workflow

For accurate prediction of the coupled thermal effect on power modules, co-simulation is performed to determine the actual junction temperature waveform within these modules, based on thermal design and switching patterns. By connecting electrical loss models with thermal impedance networks, the junction temperature rise can be dynamically evaluated.

The first step in the co-simulation procedure is to extract power loss data from the electrical simulation by using MATLAB Simulink to determine the instantaneous collector current and voltage waveforms. The switching and conduction loss per cycle is then evaluated.

The second step is to define the equivalent RC thermal network that represents the junction-to-ambient path. For instance, a three-branch foster model for a 6.5 kV SiC module might yield the values shown in the table to describe the heat spread from the semiconductor die to the heatsink.

| Branch | Rθi (K/W) | τi=RθiCth,i(s) |

| 1 | 0.015 | 0.02 |

| 2 | 0.025 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 0.040 | 5.0 |

Table 2. Sample three-branch Foster thermal network parameters extracted from transient thermal impedance data of a 6.5 kV SiC power module describing a three-branch.

The third step is to calculate the junction temperature increase by convolving the power loss profile with the transient thermal impedance. This can be numerically implemented using discrete-time convolution in tools like MATLAB or Python. The fourth step is to iterate for temperature-dependent losses, assuming an initial Tj of 25°C. Then, based on the losses, calculate the Tj(t), and update the loss parameters using the newly calculated temperature.

This process should be repeated until the temperature change between iterations is less than 1°C, indicating convergence. Finally, evaluate the thermal margin and safe operating limits by calculating the total junction temperature and plotting Tj(t) across multiple switching cycles to determine if either steady state or transient operations exceed thermal limits.

Extending the Model to Busbars and Cooling Systems

In this first part of the article, we have laid the foundation for electro-thermal modelling of high-voltage power modules, providing insights for accurate junction temperature prediction and ensuring reliable performance in high-demand 4 to 6.5 kV IGBT and SiC modules.

In the second part of this article series, we will expand on this modeling approach, examining thermal pathways in busbars and coolant channels, and developing analytical and numerical models for busbar thermal resistance. We will also examine conventional cooling equations and demonstrate how to use thermal impedance data to size a heatsink for safe, efficient operations.

With this, engineers can gain a complete understanding of how to conduct system-level thermal design for their industrial and converter systems.

Featured image used courtesy of Infineon.