A simulation framework for proton ceramic reactors could help scale hydrogen systems that run on ammonia.

A research team from Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) and the Instituto de Tecnología Química (ITQ, UPV-CSIC) has developed a low-complexity, control-oriented model that could enable real-time optimization of proton ceramic electrochemical reactors (PCERs), a promising technology for generating carbon-free hydrogen directly from ammonia.

Unlike traditional models for static simulations or detailed offline analysis, the new framework is designed for on-the-fly process control, system integration, and fault handling. That makes it one of the first dynamic reactor models aimed squarely at making green hydrogen systems practical at scale, especially those using ammonia as a low-cost, energy-dense hydrogen carrier.

The work highlights a growing intersection between electrochemical reactor design and embedded controls—a space where real-time constraints often rule out conventional CFD or FEM models.

The hydrogen lab at UPC. Image used courtesy of UPC

Why Ammonia and PCERs?

Ammonia is quickly emerging as a leading vector for hydrogen logistics due to its high energy density, well-established infrastructure, and carbon-free decomposition. Unlike compressed or liquefied hydrogen, ammonia is easier to transport and store, making it ideal for decentralized or off-grid hydrogen production.

But extracting hydrogen from ammonia safely and efficiently remains a challenge. Traditional thermal cracking requires high temperatures and downstream separation stages. Electrochemical methods like PCERs offer a more compact and efficient alternative.

PCERs operate at 400-600°C and use a solid-state ceramic membrane that selectively conducts protons. When ammonia is fed to the system, it thermally decomposes into hydrogen and nitrogen, and the hydrogen ions are transported across the membrane, yielding pure, compressed hydrogen at the output without external separation.

Still, these systems are difficult to operate. The reactor dynamics are nonlinear, thermally coupled, and sensitive to disturbances in load, temperature, and fuel composition. This is where control models become essential and where the UPC-ITQ framework enters the picture.

Inside the Control-Oriented Model

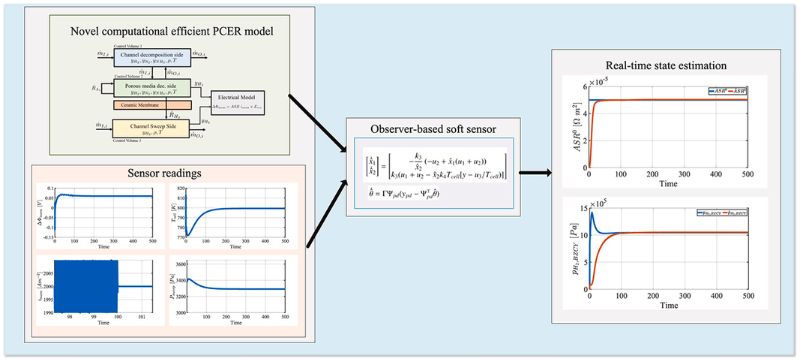

The research team developed a dynamic model of a PCER that balances physical accuracy with real-time usability. Built in MATLAB/Simulink, the framework captures the tightly coupled behaviors of ammonia decomposition, proton transport, and thermal dynamics across a dual-channel reactor layout where ammonia flows on one side, and hydrogen is extracted from the other.

The PCER framework. Image used courtesy of Cecilia et al.

At its core, the model simulates how ammonia thermally decomposes into nitrogen and hydrogen over a catalytic surface. The resulting hydrogen is split into protons, transported across a dense ceramic membrane under an applied voltage, and then recombined into pure hydrogen gas. Faraday’s law governs this electrochemical step, with overpotential losses and Joule heating folded into the system’s energy balance.

Unlike high-fidelity simulations, which are often too slow for control applications, this reduced-order model resolves species transport, voltage-current behavior, and internal heat generation fast enough to be used in digital twins, model predictive controllers, or embedded fault detection systems. Despite its speed, it captures transient behaviors like warm-up time, dynamic load following, and safe operating thresholds, laying the foundation for smarter, more responsive hydrogen systems.

Smarter, Safer Hydrogen Systems

By enabling real-time monitoring and control of ammonia-fed protonic ceramic reactors, this model helps address one of the biggest challenges in deploying hydrogen infrastructure: safe, on-demand generation at the point of use. Its speed and modularity make it well-suited for integration into distributed energy systems, off-grid hydrogen refueling stations, and decentralized industrial sites where ammonia is easier to store and transport than hydrogen.

Hydrogen refueling station. Image used courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Adaptively controlling thermal and electrochemical conditions is key to ensuring efficiency and system longevity in mobile or remote applications, such as maritime shipping, agricultural machinery, or backup power systems. Longer term, the framework could form the basis for digital twins and autonomous control loops in modular hydrogen generators, where rapid startup, thermal balancing, and fuel adaptability are essential.

As the hydrogen economy shifts from centralized production to flexible deployment, tools like this model will play a critical role in bridging the gap between lab-scale innovation and field-ready reliability.